Category Archives: Raspberry Pi

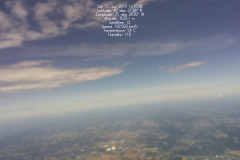

7/29/21 Balloon Launch Allentown, PA to Lafayette, NJ

7/29/22 Balloon Launch from High Point State Park

8/3/23 Balloon Launch from Cold Spring

Balloon Code V3

import os

import picamera

import serial

import time

import board

import adafruit_bmp280

import RPi.GPIO as GPIO

GPIO.setwarnings(False)

#GPIO.setmode(GPIO.BOARD)

GPIO.setup(18, GPIO.OUT, initial=GPIO.LOW)

i2c = board.I2C()

bmp = adafruit_bmp280.Adafruit_BMP280_I2C(i2c)

bmp.sea_level_pressure = 1013.25

camera = picamera.PiCamera()

camera.resolution = (1280, 720)

camera.rotation = 180

framerate = 5

camera.framerate = framerate

camera.annotate_text_size = 18

gps = "GPS Data"

gpsPort = "/dev/ttyACM0"

gpsSerial = serial.Serial(gpsPort, baudrate = 9600, timeout = 0.5)

def getPicture(annotation):

filename = "/home/pi/Pictures/" + str(time.strftime("%Y-%m-%d_%H:%M:%S", time.localtime())) + ".jpg"

try:

camera.start_preview()

time.sleep(2.5)

camera.annotate_text = annotation

camera.capture(filename)

camera.stop_preview()

except Exception as error:

return(error)

camera.stop_preview()

return filename

def getVideo(length):

filename = "/home/pi/Videos/" + str(time.strftime("%Y-%m-%d_%H:%M:%S", time.localtime())) + ".mp4"

try:

camera.start_recording("/home/pi/testVideo.h264")

for index in range(length):

start = time.time()

camera.annotate_text = (annotate())

end = time.time()

elapsed = start - end

if elapsed <= 1:

time.sleep(1 - elapsed)

camera.stop_recording()

except Exception as error:

return(error)

os.system("ffmpeg -r " + str(framerate) + " -i /home/pi/testVideo.h264 -vcodec copy " + filename)

os.system("del /home/pi/testVideo.h264")

return filename

def gpgga():

output = ""

emailgps = ""

try:

n = 1

while output == "" and n<50:

gps = str(gpsSerial.readline())

#print(n)

if (gps[2:8] == "$GPGGA" or gps[2:8] == "$GNGGA"):

gps = gps.split(",")

#lat long formatted for digital maps

latgps = gps[2][0:2] + ' ' + gps[2][2:]

longgps = '-'+gps[4][1:3] + ' ' + gps[4][3:]

emailgps = latgps+','+longgps

latDeg = int(gps[2][0:2])

latMin = int(gps[2][2:4])

latSec = round(float(gps[2][5:9]) * (3/500))

latNS = gps[3]

output += "Latitude: " + str(latDeg) + " deg " + str(latMin) + "'" + str(latSec) + '" ' + latNS + "\n"

longDeg = int(gps[4][0:3])

longMin = int(gps[4][3:5])

longSec = round(float(gps[4][6:10]) * (3/500))

longEW = gps[5]

output += "Longitude: " + str(longDeg) + " deg " + str(longMin) + "'" + str(longSec) + '" ' + longEW + "\n"

alt = float(gps[9])

output += "Altitude: " + str(alt) + " m" + "\n"

sat = int(gps[7])

output += "Satellites: " + str(sat)

n+=1

return [output,emailgps]

except Exception as error:

return ["",""]

def gprmc():

output = ""

try:

n = 1

while output == "" and n<50:

#print(n)

gps = str(gpsSerial.readline())

if gps[2:8] == "$GPRMC" or gps[2:8] == "$GNRMC":

gps = gps.split(",")

output = ""

speed = round(float(gps[7]) * 1852)/1000

output += "Speed: " + str(speed) + " km/h"

n+=1

return output

except Exception as error:

return("")

def gps():

try:

output = gpgga()[0] + "\n" + gprmc()

return output

except Exception as error:

return("")

def accurate_altitude():

try:

output = 'BMP280 Altitude: {} m'.format(round(bmp.altitude))

return output

except Exception as error:

return("")

def annotate():

timeNow = str(time.strftime("%a %d %b %Y %H:%M:%S", time.localtime()))

locationNow = gps()

bmpa = accurate_altitude()

annotation = timeNow + "\n" + locationNow + "\n" + bmpa

return annotation

def flyBalloon():

while True:

try:

getVideo(10) #40

GPIO.output(18, GPIO.HIGH)

getPicture("")

getPicture(annotate())

GPIO.output(18,GPIO.LOW)

except Exception as error:

return(error)

flyBalloon()

How Do Stepper Motors Work

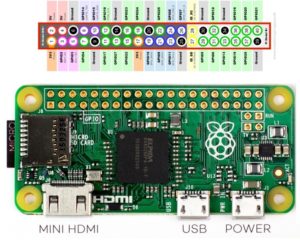

Raspberry Pi Zero Header

BMP-280 with Raspberry Pi and Python Wiring/Code

Adafruit Source

Python Computer Wiring

Since there’s dozens of Linux computers/boards you can use we will show wiring for Raspberry Pi. For other platforms, please visit the guide for CircuitPython on Linux to see whether your platform is supported.

Here’s the Raspberry Pi wired with I2C:

|

|

|

And an example on the Raspberry Pi 3 Model B wired with SPI:

|

|

|

CircuitPython Installation of BMP280 Library

You’ll need to install the Adafruit CircuitPython BMP280 library on your CircuitPython board.

First make sure you are running the latest version of Adafruit CircuitPython for your board.

Next you’ll need to install the necessary libraries to use the hardware–carefully follow the steps to find and install these libraries from Adafruit’s CircuitPython library bundle. Our CircuitPython starter guide has a great page on how to install the library bundle.

For non-express boards like the Trinket M0 or Gemma M0, you’ll need to manually install the necessary libraries from the bundle:

- adafruit_bmp280.mpy

- adafruit_bus_device

Before continuing make sure your board’s lib folder or root filesystem has the adafruit_bmp280.mpy, and adafruit_bus_device files and folders copied over.

Next connect to the board’s serial REPL so you are at the CircuitPython >>> prompt.

Python Installation of BMP280 Library

You’ll need to install the Adafruit_Blinka library that provides the CircuitPython support in Python. This may also require enabling I2C on your platform and verifying you are running Python 3. Since each platform is a little different, and Linux changes often, please visit the CircuitPython on Linux guide to get your computer ready!

Once that’s done, from your command line run the following command:

sudo pip3 install adafruit-circuitpython-bmp280

If your default Python is version 3 you may need to run ‘pip’ instead. Just make sure you aren’t trying to use CircuitPython on Python 2.x, it isn’t supported!

CircuitPython & Python Usage

To demonstrate the usage of the sensor we’ll initialize it and read the temperature, humidity, and more from the board’s Python REPL.

If you’re using an I2C connection run the following code to import the necessary modules and initialize the I2C connection with the sensor:

- import board

- import busio

- import adafruit_bmp280

- i2c = busio.I2C(board.SCL, board.SDA)

- sensor = adafruit_bmp280.Adafruit_BMP280_I2C(i2c)

Or if you’re using a SPI connection run this code instead to setup the SPI connection and sensor:

- import board

- import busio

- import digitalio

- import adafruit_bmp280

- spi = busio.SPI(board.SCK, MOSI=board.MOSI, MISO=board.MISO)

- cs = digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.D5)

- sensor = adafruit_bmp280.Adafruit_BMP280_SPI(spi, cs)

Now you’re ready to read values from the sensor using any of these properties:

- temperature – The sensor temperature in degrees Celsius.

- pressure – The pressure in hPa.

- altitude – The altitude in meters.

For example to print temperature and pressure:

- print(‘Temperature: {} degrees C’.format(sensor.temperature))

- print(‘Pressure: {}hPa’.format(sensor.pressure))

For altitude you’ll want to set the pressure at sea level for your location to get the most accurate measure (remember these sensors can only infer altitude based on pressure and need a set calibration point). Look at your local weather report for a pressure at sea level reading and set the seaLevelhPA property:

- sensor.sea_level_pressure = 1013.25

Then read the altitude property for a more accurate altitude reading (but remember this altitude will fluctuate based on atmospheric pressure changes!):

- print(‘Altitude: {} meters’.format(sensor.altitude))

That’s all there is to using the BMP280 sensor with CircuitPython!

Here’s a starting example that will print out the temperature, pressure and altitude every 2 seconds:

- import time

- import board

- # import digitalio # For use with SPI

- import busio

- import adafruit_bmp280

- # Create library object using our Bus I2C port

- i2c = busio.I2C(board.SCL, board.SDA)

- bmp280 = adafruit_bmp280.Adafruit_BMP280_I2C(i2c)

- # OR create library object using our Bus SPI port

- #spi = busio.SPI(board.SCK, board.MOSI, board.MISO)

- #bmp_cs = digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.D10)

- #bmp280 = adafruit_bmp280.Adafruit_BMP280_SPI(spi, bmp_cs)

- # change this to match the location’s pressure (hPa) at sea level

- bmp280.sea_level_pressure = 1013.25

- while True:

- print(“\nTemperature: %0.1f C” % bmp280.temperature)

- print(“Pressure: %0.1f hPa” % bmp280.pressure)

- print(“Altitude = %0.2f meters” % bmp280.altitude)

- time.sleep(2)

Protected: Flight of the George!

GPS Code for USB Receiver

import serial

gpsPort = "/dev/ttyACM0"

gpsSerial = serial.Serial(gpsPort, baudrate = 9600, timeout = 0.5)

def parseGPS(data):

gps = data

try:

if gps[2:8] == "$GNGGA":

gps = gps.split(",")

timeHour = (int(gps[1][0:2]) - 4) % 24

timeMin = int(gps[1][2:4])

timeSec = int(gps[1][4:6])

print("Time: " + str(timeHour) + ":" + str(timeMin) + ":" + str(timeSec))

latDeg = int(gps[2][0:2])

latMin = int(gps[2][2:4])

latSec = float(gps[2][5:9]) * (3/500)

latNS = gps[3]

print("Latitude: " + str(latDeg) + "°" + str(latMin) + "'" + str(latSec) + '" ' + latNS)

longDeg = int(gps[4][0:3])

longMin = int(gps[4][3:5])

longSec = float(gps[4][6:10]) * (3/500)

longEW = gps[5]

print("Longitude: " + str(longDeg) + "°" + str(longMin) + "'" + str(longSec) + '" ' + longEW)

alt = float(gps[9])

print("Altitude: " + str(alt) + " m")

sat = int(gps[7])

print("Satellites: " + str(sat))

if gps[2:8] == "$GNRMC":

gps = gps.split(",")

speed = float(gps[7]) * 1.852

print("Speed: " + str(speed) + " km/h")

head = float(gps[8])

print("Heading: " + str(head))

else:

gps = ""

except Exception as error:

print(error)

return gps

while True:

print(parseGPS(gpsSerial.readline()))